Distributed Denial of Justice: Serbia's Stealth Surveillance Arsenal Spearheads Civil Repression

The Land that Justice Forgot

August 25th, 2000 was a sunny day in Belgrade. The last rays of the summer sun hit the yellowed out walls of Yugoslav-era apartment buildings, contrasting with the ambient greyness of a country that had welcomed summertime while under NATO bombs. Serbia had been under crippling sanctions for the better part of the 1990s as the ruling Socialist Party of Serbia's (SPS) aggressive stance during the Yugoslav wars had deeply impoverished, divided, and damaged the country. Yet, riding the city's derelict buses and swarming around bridges destroyed by the NATO bombing, Belgrade's citizens expressed a sense of optimism: less than a month separated them from presidential elections where, for the first time in a decade, President Slobodan Milošević could be beaten. Activists of the DOS (demokratska opozicija Srbije), a heterogeneous alliance of parties opposed to Milošević, plastered the city with posters calling for citizens to defeat the President at the ballot box.

Away from the bustle of downtown Belgrade, Ivan Stambolić was out at the Košutnjak national park on his daily run. As President of the Socialist Republic of Serbia, Stambolić was once Milošević's mentor within the ruling League of Communists of Yugoslavia and facilitated the young banker's rise through the party's ranks. Milošević thanked him by unceremoniously betraying him in 1989, making the Central Committee vote to expel Stambolić from the Party. After three failed wars in the former Yugoslavia, record-breaking inflation, and significant human costs, Milošević's string of luck seemed to have finally run out. As Stambolić's heart rate increased and his pace quickened, was he gazing at the national park's foliage, thinking about this irony of history? Rumour had it that he was considering a comeback once Milošević lost the elections.

Whether this was true or what Stambolić was thinking this morning will forever be a mystery to us: he vanished after his jog. His body was only found in 2019 over 80 kilometres away from the Košutnjak park, buried in a makeshift quicklime pit and with two bullets lodged in his head. This apparent gangland hit was actually the work of special police units of the Serbian Ministry of the Interior. While some of the executors were eventually sentenced, those that ordered Stambolić's murder have never been identified, prosecuted, or convicted. Slobodan Milošević died of heart failure at the Hague in 2006, while his mentor joined the list of dozens of journalists and regime opponents that suspiciously died during the 1990s in Serbia and still have not received justice.

The inability or unwillingness of states to prosecute individuals for crimes committed at the behest of past regimes is a common feature of post-Socialist Eastern Europe. As these states democratized, many failed to reform Socialist-era security services, which became facilitators between the world of politics, business, and organized crime. Under the rule of the Serbian Progressive Party (SNS; Srpska napredna stranka), the Serbian Ministry of the Interior has been operating as a protector of President Aleksandar Vučić's regime. The SNS has routinely used its agents, but also criminal groups and football hooligans, to intimidate journalists, magistrates, and opposition politicians. Smear campaigns of opposition figures regularly take place in private medias owned by figures friendly to Vučić and SNS cadres. Meanwhile, Serbia was becoming a global leader in the acquisition and extralegal use of sophisticated surveillance products.

From Purchase to Practice

In the fall of 2023, the European Union (EU) was taking stock of spyware scandals taking place in a number of member-nations. In October 2023, a month before parliamentary elections were set to take place in Serbia, the Toronto-based Citizen Lab warned of evidence that the NSO Group's Pegasus spyware was used against two members of civil society vocal in their criticism of Vučić. They promptly contacted AccessNow and Amnesty International, who corroborated Citizen Lab's hypothesis of Pegasus abuse.

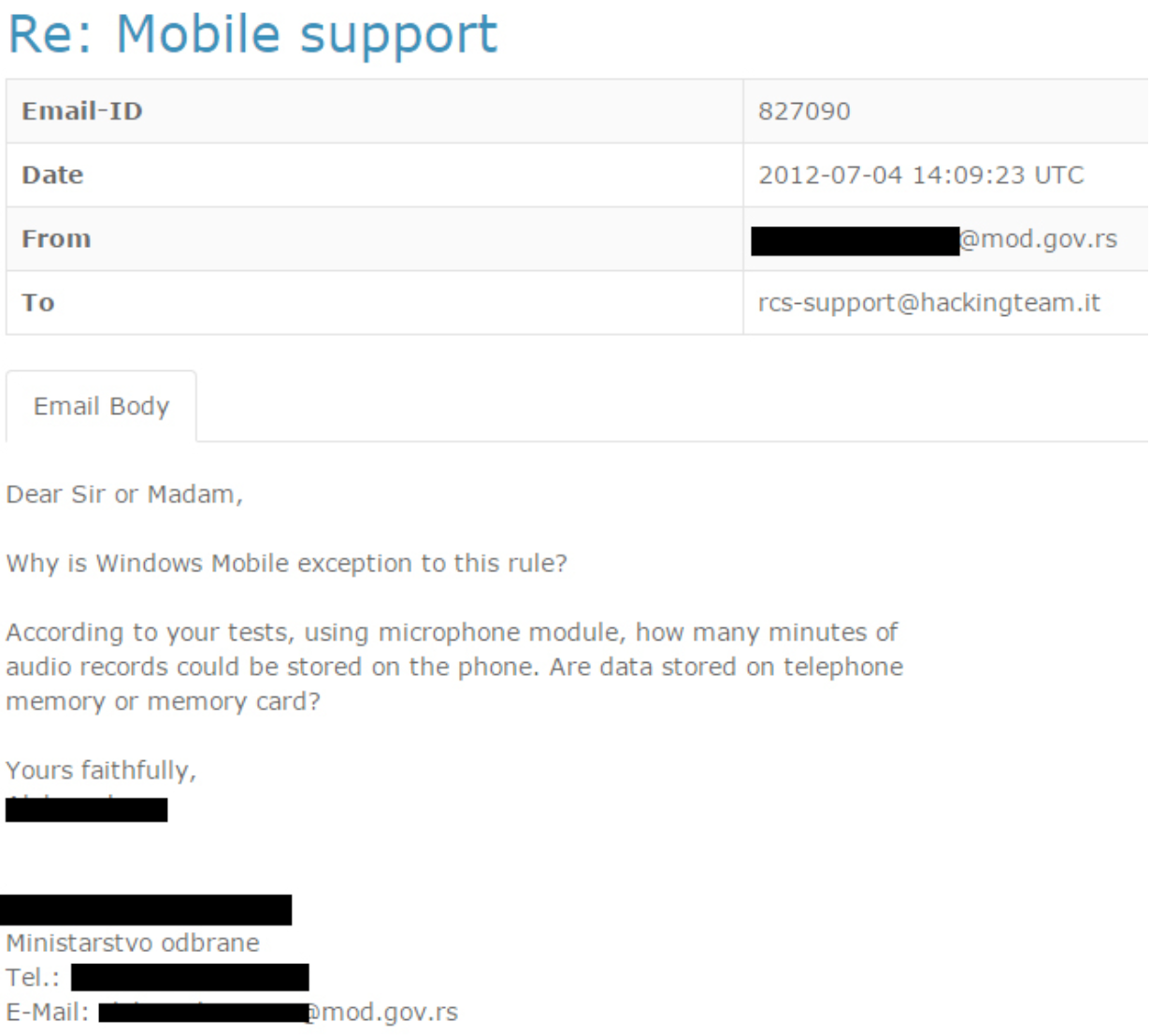

Serbia's civil intelligence agency, the Security Intelligence Agency (BIA; bezbednosno-informativna agencija) has been known as the main consumer and operator of spyware in the country. The BIA's surveillance bulimia dates back to 2012 at the very least, with leaked emails revealing that it had received demonstrations for the Milan-based Hacking Team's spyware product.

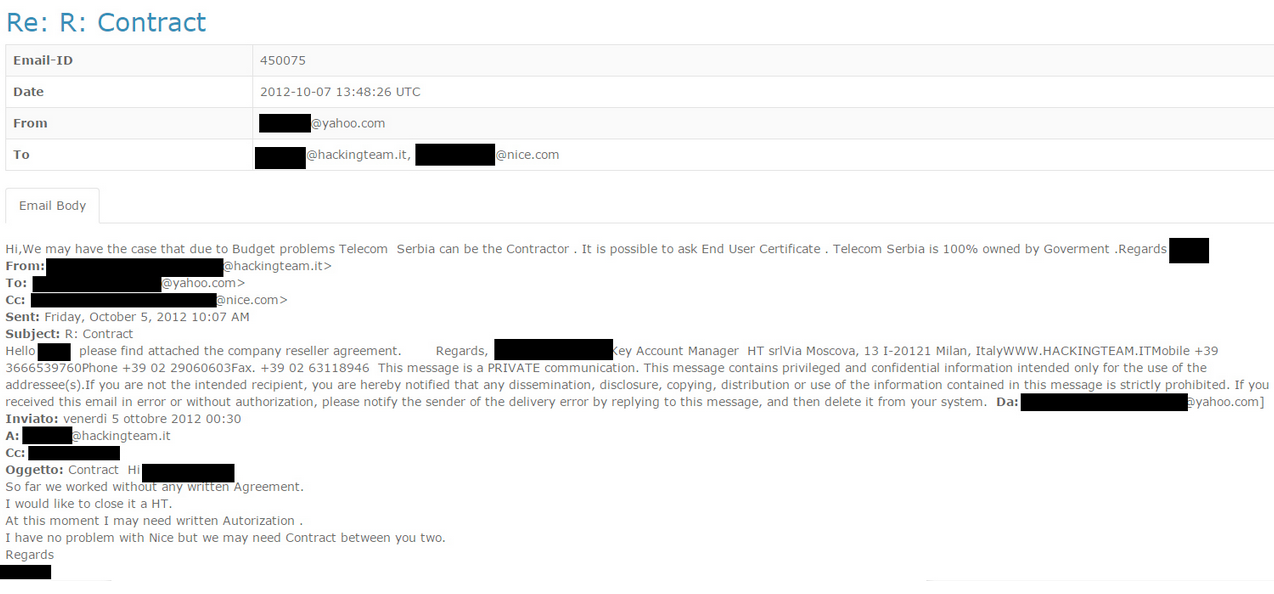

In 2015, Citizen Lab has identified the BIA as a customer of FinFisher, a surveillance software known for its sale to a swathe of regimes with dubious human rights records. The Citizen Lab also observed FinFisher servers in the state-owned telecommunications provider Telekom Srbija. Telekom Srbija also appears to have been used as a front to procure spyware from the Hacking Team.

Other state-owned agencies, such as Serbia's hydroelectric distribution body, have also acquired surveillance materials without there ostensibly being a need for them to own such technologies. This points to the Serbian state not only being willing to purchase highly intrusive surveillance technology, but having an established network of front agencies and companies through which these goods can transit. Generally, governments do not buy directly from the makers of products such as Pegasus, preferring to deal with a network of middlemen and shell companies. In Serbia, this role is played by organizations such as IntellSec and Lanus Limited (currently known as Devellop Limited). Vlatacom Limited, on the other hand, purchases these goods for the Serbian state while also designing and selling their proprietary surveillance software. Other surveillance products purchased by the BIA were made by the NSO Group partner Circles, Clearview AI, Cyberbit Mercenary Spyware, and the Griffeye facial recognition software. All of these products or entities have come under national or global scrutiny for the power of their intrusive technologies and their willingness to sell to deeply repressive regimes.

A final thought must be given to the Serbian state's use of the Predator spyware. In 2021, the Citizen Lab detected the presence of the Predator spyware in Serbia operated from domains tied to Serbian newspapers. These findings were confirmed by Google's Threat Analysis Group.

Cytrox, the maker of Predator, is based in the country of North Macedonia and has corporate presences in Hungary and Israel. As of the writing of this article, Predator is responsible for a number of documented civil rights abuses, enabling authoritarian rulers across the globe to spy on their political opponents, and has even been detected on battlefields. Cytrox's CEO owns a restaurant in North Macedonia, where he also discusses tenders for weapons and military hardware with the country's top political brass. Even for spyware, patronage and corruption are musts for decision-making in the Balkans.

Big Brother in Belgrade

The 2023 wave of spyware infections posed the question of foreign influence in Serbia. Spyware investigations are notoriously secretive and convoluted, making definite conclusions regarding its operators difficult. At the time, the head of the BIA was Aleksandar Vulin, a Vučić loyalist known for his divisive and ethnically inflammatory statements. Aside from being comically corrupt, once trying to justify €205,000 used to purchase his lush Belgrade apartment as a loan from an aunt in Canada, Vulin is known for his close ties with arms dealers. In his role, Vulin acts as a mouthpiece for the Kremlin, to the extent that the Biden administration officially designated him as a corrupt official in 2023. In 2021, the BIA recorded meetings of Russian opposition politicians in Belgrade, with Vulin allegedly passing the tapes to high-ranking officials in the Russian state. The state-visit during which Vulin visited Moscow preceded the arrest of Russian civil society members and opponents to Vladimir Putin.

If, indeed, surveillance has become a bargaining chip of global affairs, no other country has flexed its muscles before the Western world as China. Serbia emerged as the surprise leader in the response to the COVID-19 pandemic: only beaten by the United Kingdom in terms of vaccinations per capita in 2021 and was one of the first countries to declare a state of emergency and curfews statewide. By far though, Serbia led other countries in surveilling its citizens to ensure compliance with COVID restrictions. Just as it had helped with supplying its vaccines for COVID, China was happy to help on the surveillance front; only a year after COVID, Belgrade was on track to be the first European capital with public spaces practically fully covered by Chinese cameras.

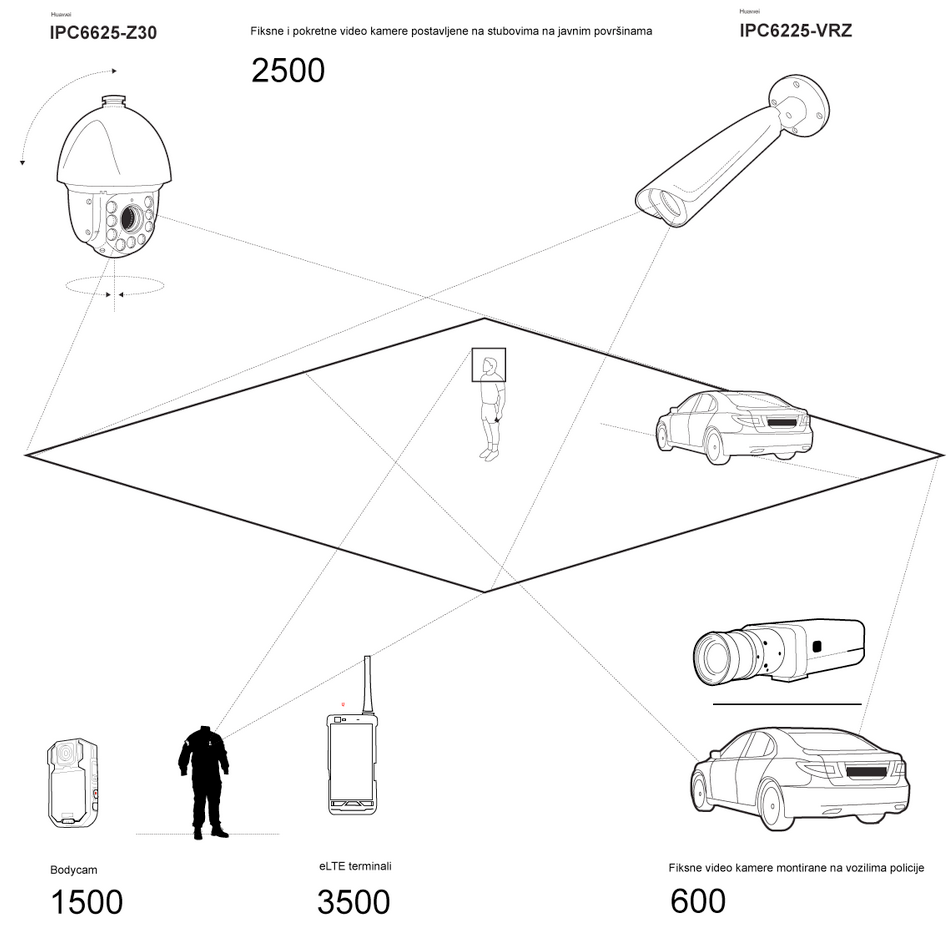

This opportunity gave Beijing the chance push their so-called "smart cities" while also furthering its influence in the Balkans and Europe. Chinese soft power has been furthered for some time by the country's IT companies, these are legion in the project to mould Belgrade into a smart city, including Huawei, ZTE Corporation, Hangzhou Hikvision Digital Technology, Zhejiang Dahua Technology, Alibaba, and other undisclosed entities. It has to be said that the process to fit Belgrade's cameras with Chinese biometric technology was clouded in mystery from the start. The Ministry of the Interior withheld privacy and human rights analyses conducted before implementation, camera locations also remained undisclosed as did any information on the procurement process. Activisits fought against the secrecy, creating accounts on X to keep track of the biometric cameras installed at breakneck pace in Serbia's capital. Commenting on the revised version of the data protection impact assessment, the SHARE Foundation notes that more than 8,000 cameras will be used to monitor Belgrade. Their review highlights that these include body cams attached to uniforms, mobile cameras, and vehicles:

The updated DPIA states that biometric surveillance will take place, affecting all persons walking through an area overseen by the video surveillance system. The Ministry of the Interior states that the system will be used for profiling without defining what this exactly means. It is also disclosed that data can be distributed to "authorized recipients", whose definition is quite broad, and that facial recognition software can be used to protect the life, health, and other "vital interests" of data subjects.

Such wording gives room for a liberal interpretation of the assessment, but, then again, biometric mass surveillance is not allowed by the Serbian Law on Personal Data Protection. Specifically, Article 5 mandates that data processing must be proportionate in line with the purpose, while balancing public and private interests and freedoms. Articles 17 and 38 respectively ban processing of biometric data due to the sensitivity of captured data and prohibit automated decisions in processing any type of data. The Ministry of the Interior is the data controller for the surveillance system, making it responsible for ensuring the lawful processing of all personal data. All the data from the system is stored at the Ministry’s command and operations center, the police further have the authority to use information gleaned from the system for law enforcement purposes. Despite a new government taking office after elections in 2020 and a new interior minister being appointed, both remain controlled by the same ruling coalition led by the SNS.

In sum, the Serbian state has created a legal framework seemingly implementing guardrails against the abusive use of surveillance technology, but which actually facilitates its use. Observers further note that Chinese facial recognition technology is often exported to shaky democracies like Serbia, ultimately exporting its own model of governance abroad. Ultimately, it's in Beijing's interest to have a friendly partner in Belgrade to maintain the contracts awarded to its state-owned firms. It's also in the Vučić regime's interest to keep a watchful eye over dissenters and steps taken to oppose its grip on power. The impetus for Serbia's introduction of advanced surveillance during COVID were relentless protests against the lock down conditions. Bills to legalize surveillance coincided with unprecedented demonstrations across the country against the SNS' intention to allow Rio Tinto to excavate swathes on land in Eastern Serbia. It's worth noting that the Serbian Ministry of Interior works with its Russian counterpart to counter popular uprisings; even having sought specialized cybersecurity training from Moscow.

Eyes Everywhere, Justice Nowhere

At first glance, there does not seem to be much in common between Ivan Stambolić's death and spyware infections of Serbian opposition figures. The former ended in death and was the handiwork of thugs operating in the framework of a perverted state-security apparatus. The latter cannot necessarily be tied to physical harm as yet and takes place remotely. Definite attribution of spyware attacks is very difficult to do and researchers must rely on indicators of compromise, known tactics and techniques, and, most importantly, victims willing to come forth and offer their devices for forensic analysis in a timely manner. Spyware case don't fare well in courts either: victims are understandably reluctant to come forth given what sensitive information spyware may have gotten from their mobile devices. In the end, there is no one to charge and, just as in the Stambolić case, justice cannot be served.

At a time where trust in institutions is eroding across the world, the Serbian case remains instructive. It shows that state with weak institutions are fertile ground for the usage of intrusive surveillance technologies. It displays how these technologies need murky ecosystems of shell corporations and fronts to thrive and proliferate. It demonstrates how governments can depict democratic protesters as fifth columnists sold to a foreign adversary, weaponizing fears of instability, resulting in regime changes to introduce sweeping surveillance programs. Most importantly, it shows how great powers can use this desire for control to encroach closer on their strategic adversaries' turf. As these different actors mobilize to pursue their own goals, civil rights are eroded, mass collection of data and personal information is normalized, and society is permeated with a climate of fear and suspicion. The widespread use of these technologies might ultimately be more successful at shutting down democracy than pedophiles or organized crime groups.

A month ago, a roof collapse at the Novi Sad bus station caused the death of fifteen Serbian citizens. Since then, members of Serbian civil society haves been in the streets protesting the evasive answers from the ruling SNS on the station's management and corruption that would have contributed to the tragedy. As usual, after a few high-profile feigned resignations, the SNS retaliated savagely—: character assassinations against protesters, fake news on the movement, and misleading headlines abound on Serbian private and state media. Earlier this week, we learned of the Serbian police using Cellebrite and bespoke Android spyware systems to infiltrate the mobile devices of investigative journalists. What's more, these phones were infected as users visited the offices of the BIA to report suspected hackings of their mobile devices. Once more, a high-profile event in Serbia led to demonstrations and then to reports of spyware being used. This time, the protests are still going strong and have spread to universities in Belgrade, Novi Sad, Niš, and Kragujevac. Whether they will wrest meaningful change from a BIA doped on surveillance technologies remains to be seen, as is true for whether the fifteen dead in the bus station will receive justice.